Jiggling the Jing

How do we cultivate inner stillness, powerful healing presence, mastery of medicine (perhaps even with a capital “M”) beyond technique, or whatever you want to call it? We were playing with concepts like “concentrating the yì (intent) and unifying the shén (spirit/s), to stop the jīng essence and Qì from separating, …so as to gather in the (patient’s?) jīng (essence)” 專意一神,精氣不分…以收其精 (Lingshu 9). In this context, Leo mentioned the phrase 搖精 yáo jīng, which I have, somewhat fancifully, translated in the title of this short article as “jingling jīng,” but which you could also render as “rattling the essence.”

Moderating the Liver?

For the past two weeks, much of my attention has been taken up by a course on “Nurturing the Fetus: The Ten Months of Pregnancy in the Chinese Medicine Classics and the Modern Clinic,” which I am currently teaching with my clinical colleague and friend Andrew Loosely. A student in that class had a great question about the recommendation for the first month of pregnancy. Here is the information and advice, as worded in one of our sources, Bèijí qiānjīn yàofāng 2.3 《備急千金要方》…

Withdrawing Epilepsy

How do you choose between different meanings of a single character when you are working on a particular passage and the answer is not immediately obvious? This is a common problem that anybody who is trying to read classical literature has to confront on a regular basis. The importance of this challenge to find the correct meaning in a specific context is obvious, especially when we are dealing with clinical literature like indications for formulas or medicinals. In today’s post, I shall use the Shénnóng běncǎojīng 《神農本草經》 (“Divine Farmer’s Classic of Materia Medica”) to introduce you to my world of navigating this challenge and arriving at what I consider the best decisions at any given moment.

My Good Friend Yùexìn

Each of us may just be a drop of water in the ocean of popular and biomedical discourse on “The Curse,” but bit by bit, one conversation at a time, we can take the “s” out of that awful term and think of it more like the sweet casual Chinese term 我的好朋友 “my good friend.”

Why Learn Classical Chinese?

…I am convinced that classical Chinese has a way of accessing the deeper truths in nature, in heaven and earth, and in the human condition, that no modern language could ever express. It has a way of playing with layers of meaning in each character, with dimensions and relationships, of evoking feelings and connections between overlapping and actively interacting fields of reference. I am further convinced that we, by studying it and reading it, can slowly begin to acquire the ability to perceive the world in such a non-rational, non-linear, heart-centered mode that we can then apply to whatever aspect of truth we are interested in, whether it be medicine, aesthetics, gardening, wood-working, or parenting. …

Wallowing in Words

Yes! There are paths that can be followed as paths

But! These are not the paths that last.

Ming: Names

Yes! There are names that can be employed as names

But! These are not the names that last.

Suwen 5 and Seeking the Root

…the lesson here is that we all need to stay open to learning and being corrected. That none of our knowledge is ever enough, that we all make mistakes, and that we all must create and maintain and nurture a learning environment that facilitates this sort of mutual collaboration. And that we must hold each other accountable, and that that our goal must be not to make ourselves right and the other person wrong but to learn from and with and for each other, for the benefit of the greater good.

Sun Simiao on Yangxing

Now, it is difficult for humans to nurture but easy to imperil, as it is difficult for Qì to be clear but easy to be turbid. Only when we are able to fully know our awe-inspiring virtue-power in order to protect the spirits of the earth and of the grain, and when we are able to sever our desires in order to secure the blood and Qì, only then will the True One be preserved therein, will the Three Ones[2] be safeguarded therein, will the hundred diseases turned back therein, and will longevity be extended therein…

Chao Yuanfang on Epidemics

The following is my translation of Cháo Yuánfāng’s 巢元方 three essays on Epidemics, found as Volume 10 of the Zhūbìng yuánhòu lùn《諸病源候論》(“Discussion of the Origins and Signs of the Various Diseases,” from 610 CE)

Embracing the Middle

Mengzi: “Yangzi chooses acting on his own behalf, which means that if he could benefit all Under Heaven by pulling out even a single hair, he still would not do it. Mozi practices universal love, which means that if he had to rub himself raw from the top of the head to the heel of the foot to benefit Under Heaven, he would still do it. Zimo embraces the middle, which brings him closer. However, embracing the middle without expediently adapting to circumstances is still a form of embracing a single position. The reason why I dislike embracing a single position is because it strong-arms the Dao and because it elevates a single position and dismisses a hundred others.”

Establishing Life Through Water and Fire

My translation of ̌Shuǐ huǒ lìmìng lùn 水火立命論 (Treatise on Establishing Life Through Water and Fire), by Cài Yíjì 蔡貽績 from the Qing dynasty: “How are humans created? Humans are created in fire. They are created in the [third earthly branch] Yīn, which is fire. Fire is the substance of Yáng. Creation takes Yáng as the root of life. Human life takes fire as the gate of the lifespan (mingmen). Scholars say that heaven opens in [the first heavenly branch] Zǐ, and that Zǐ is the origin. Doctors say that humans are created from water, and that the kidney is the origin. Who is aware that Zǐ is the beginning of Yáng and that the kidney constitutes a fire organ/storage?…

A Heart Full of Great Compassion

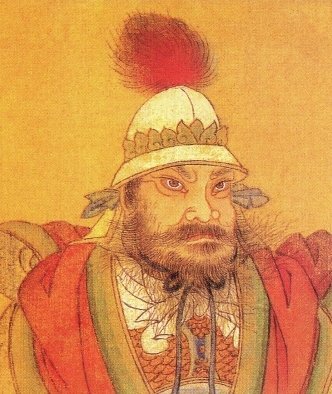

Known in China and abroad as the “King of Medicinals,” Sun Simiao 孫思邈 is one of the most celebrated figures in the long history of Chinese medicine. He is also the author of China’s first – and still relevant – essay on medical ethics and professional cultivation, which is included in countless oaths of TCM schools worldwide. Despite Master Sun’s elevated status in both China and the West as one of its greatest practitioners, however, an official biography composed several centuries after his death and other historical documents offer not a single hard fact about his professional practice as a physician. To appreciate the significance of this fact, we need to look both at the context of medical practice in early China and the content of Sun Simiao’s teachings. With this understanding, we shall be prepared to read his famous essay “On the Sublime Sincerity of the Eminent Physician,” which I have translated below.

Tinier than Autumn Down

In honor of the transition to the New Year of the Metal Rat and my final writing efforts of the Pig Earth year, here is little taste from the Introduction to my forthcoming Channeling the Moon, Part Two: A Translation and Discussion of Qí Zhòngfǔ’s Hundred Questions on Gynecology, Questions 15-50, which addresses miscellaneous conditions of gynecology. The following is the literal translation of a quotation from Chén Zìmíng’s 陳自明 introductory essay of the Fùrén dàquán liángfāng 《婦人大全良方》 (Compendium of Excellent Formulas for Women) composed in 1237

The Yin and Yang of Education

Being an educator in the field of classical Chinese history, culture, and medicine, it is impossible for me to avoid a critical engagement with the topic of education spanning three areas: as envisioned in classical Chinese philosophy and politics, as practiced in various forms throughout the history of Chinese medicine, and as enacted today in both institutional and private educational settings…

Classical Chinese Sleep Hygiene

This brief exploration of advice on sleep hygiene from classical Chinese medical and Daoist texts originated with my translation project on the “Hundred Questions on Gynecology.” In Question 49 on the “Thirty-Six Diseases Below the Belt,” the author discusses “harm from sleeping” as one of the seven harms that cause women’s illnesses. When a curious reviewer of my manuscript asked me to explain, I had to go down that rabbit hole, at least briefly. Here is what I found and write in my discussion…

Women’s Health in Medieval Manuscripts

In contrast to the beginnings of classical Chinese medicine in the Han period, our knowledge of early medieval medicine is still sketchy. This is due largely to a lack of sources. Of the more than 100 medical texts recorded in the Old Tang History (Jiùtángshū 《舊唐書》, 945 CE), only four have survived in the received literature from the early medieval period: Cháo Yúanfāng’s 巢元方 Zhūbìng yuánhòu lùn 《諸病源候論》 (On the Origins and Symptoms of the Various Diseases, 610 CE), Sūn Sīmiǎo's 孫思邈 Bèijí qiānjīn yào fāng 備急千金要方 (Essential Formulas worth a Thousand in Gold for Every Emergency, 652 CE, in the following discussion abbreviated as Qiānjīnfāng), his Qiānjīn yìfāng 千金翼方 (Supplementary Formulas worth a Thousand in Gold, 682 CE), and Wáng Xī’s Wàitái mìyào 外台秘藥 (Essential Secrets From the Palace Library, 752). Other texts are known only from quotations in compendiums like the Japanese Ishimpō 醫心方 (Prescriptions from the Heart of Medicine, 984 CE), a collection of early medieval Chinese medical literature by a Japanese court acupuncturist. The other great source for medical literature from this period is the corpus of medical manuscripts found in Dūnhuáng 敦煌, which date mostly to the Suí and early Táng periods.

Questioning Menopause Part Two

MENOPAUSE PART TWO: WHAT’S IN THE TEXTS?

How do the Chinese classics talk about menopause? To be meaningful, our inquiry has to be expanded a little beyond the obvious and technically correct answer: Since the concept of “menopause” does not even exist in traditional Chinese medicine or language, the medical classics do not talk about it at all.

That may be the case, strictly speaking, if we define “it” narrowly as the “pathology of age-related cessation of monthly bleeding.” As contemporary practitioners of Chinese medicine in our modern biomedicalized society, however, we still need answers for our friends, family members, and patients who come to us with conditions that they experience as pathological. So how do the classical texts discuss the aging process of women, especially in contrast to that of men? And how might these descriptions be used in the contemporary context?

Lower Leg Qi

The following is another excerpt from my ongoing translation project, the “Hundred Questions of Gynecology” 女科百問 by Qí Zhòngfǔ from 1220 CE. “Question Twenty-Nine: What is the Reason for Women Suffering from Pain in the Ten Toes as If They Were Being Fried in Oil, and Experiencing Heat Pain When Covered up and Cold Pain When Exposed to Blowing Wind?” … The key points to take away from earlier medical literature on the disease of Lower-Leg Qì are as follows: It is a condition that can express itself in numerous ways and does not have a single cause or even key symptoms. Nevertheless, it is, at least was originally, associated with pathological wind that invades the body through the feet. …

Sun Simiao on Fertility

The following is an excerpt from the 75-page historical introduction to my newest publication Channeling the Moon, a translation and discussion of the first fourteen questions of Qí Zhòngfǔ’s 齊仲甫 Nǚ Kē Bǎi Wèn 女科百問 (“Hundred Questions of Gynecology,” published in 1220 CE). This excerpt includes a brief introduction to the Bèi Jí Qiān Jīn Yào Fāng 備急千金要方 (composed by Sūn Sīmiǎo 孫思邈 in 652) and a survey of Sūn Sīmiǎo’s ideas on fertility. For more on early Chinese gynecology and fertility, see the information page for my book Channeling the Moon in my ONLINE BOOKSTORE HERE. The photographs below, most of which have also made it into the book, are from around my home on Whidbey Island, but here you get the colored version.