Wallowing in Words

Originally published March 22, 2021

Alternate Title: Having a Whale of a Time with Translation

Translation is just one form of communication, and some recent conversations in my advanced classical Chinese class, followed by a dream of eating Schnitzel in Tel Aviv (which will have to be explained in another post) have inspired me to think more critically about what I do all day long when I try to bring Sun Simiao’s writings on “nurturing the Heavenly nature” from 7th century China into my 21st century studio on Whidbey Island.

How do I communicate with the neighborhood deer so that they leave my young apple trees alone? I cannot tell you, but I do know that the only time over the past three years that they have taken a nibble was last spring when I was out of town to help my daughter graduate from college in this pandemic. And the deer do pass through, even saying hi to my sweet old dog. Now, cross-species communication has its challenges, I am the first to admit, as a bee sting on my eye reminded me in a very painful lesson because I had rudely tried to sneak into my new friends’ home through the chimney instead of knocking politely on the front door, and got caught in the act. My old bees, years ago in New Mexico, were used to my intrusions, I suppose, but these guys are definitely more touchy. I try to tell Old Man Heron to ignore us as the dog and I walk by his patch of the beach and sometimes he gets the message, but other times he flies off with a nasty screech, and I feel bad that we have disturbed him. Playing hide and seek with a seal who I so want to make friends with is fun for the seal but always gets cut short by my lack of blubber in these frigid waters.

After a year of pandemic isolation, talking to our pets is thankfully no longer considered all that strange, and it feels great to know that I am not the only one singing to my goats during milking time. But besides biodynamic farmers, little old ladies in funny hats, and flower essence producers (who may all be one and the same anyway), how “normal” is it to talk to your friends Cedar or Rose or the first dandelion in the spring, which I just noticed today? Or even further out there, a couple of months ago during a late night walk in the woods, a certain star named Alcor (輔 fǔ in Chinese), located on the handle of the Big Dipper, was definitely expressing to me stern displeasure with ignoring its presence in the Chinese title of the source text for my latest publication (輔行訣臟腑用藥大要) and casually entitling my book Celestial Secrets.

How do we know what we know and don’t know and how do we each form our knowledge about the world? Are some of us, the ones with active “imaginations” perhaps, just making things up, as more literal-minded people might argue, or have failed to grow out of, or reverted back to, a child’s inability to differentiate between what is real and what is not? Confucius once explained to his disciple what it means to know in this way:

知之為知之。 不知為不知。是知也。

If you know it, act on knowing it; if you don't know it, act on not knowing it. This is what it means to know!"

But at what point does this question stop even being important in the first place? The older I get, and the more time I spend in coronavirus quarantine with my wild and domesticated animal and plant companions on my little island, the less I care what other humans think, and the more I respond only with curiosity and gratitude, and perhaps a sprinkling of humor, when I get strange messages seemingly out of nowhere. I do know to honor my dreams and receive them with deference as gifts from that realm that human language cannot access, whether we call it our higher self, the beyond, the other dimension or whatever.

Since many of us are going through a challenging time right now and I don’t want this post to get too heavy, here is my all-time favorite commentary on translation issues: the famous German coast guard ad by a German language school. This one never gets old for me.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x9wJxZc2KF8

Okay, back to translation. Wonderful challenging questions and a deep discussion on the art of translation with my classical Chinese students made me realize that for me, translation is a dance between right and left brain as well as between brain and heart and Shén (spirit/s), contraction and expansion of meaning, dreaming and analysis, space and structure, floating and submerging in resonance with cosmic waves. All too often, I sense a certain rhythm that then needs to find matching words, a worldview, an eagle’s perspective that zooms in and in and in from one’s way of being in the cosmos, to culture, to social interactions, to family environment, personal preferences, to the literary context, syntax and grammar rules, and then, at last, to the choice of individual terms.

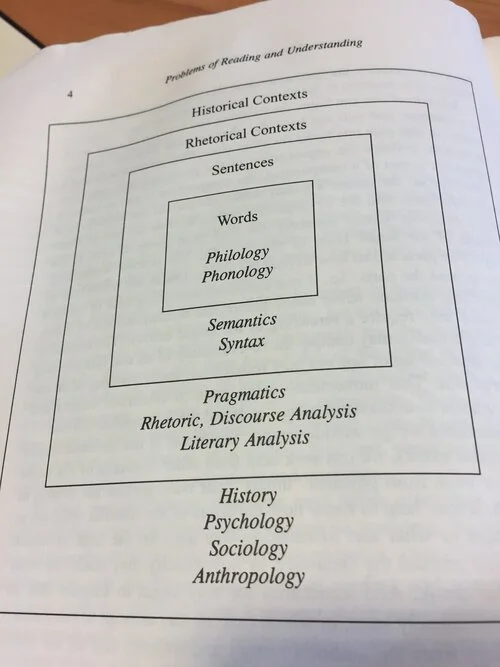

I keep returning to the diagram to your left, found on p. 4 of Michael A. Fuller’s Introduction to Literary Chinese. What I have noticed far too often in Chinese medicine circles is that self-taught hobby translators tend to focus only the smallest box in this diagram, namely the individual terms and their etymology, which is, of course, an essential aspect of reading an ancient Chinese text but far from the only one. In fact, finding the appropriate English word for each Chinese character turns out to be such a small part of crafting an accurate representation of any classical Chinese passage, to the extent that that is even possible at all.

To complicate matters, is it fair to say that Western languages, and one could argue even modern Chinese, endeavor or have at least evolved to impose order or structure on the formless and wordless cosmic rhythms resonating in our minds, as a means of communication? And if so, how is classical Chinese different? Hasn’t the goal of communication always been to share what we are sensing, our way of experiencing, making sense of, and aligning with the Dao, with the changes in the world around us, and expressing that to each other? Or is it not? What changes when we question that assumption?

Why does the bird outside my window sing at sunrise? Right now, he is not attracting a mate, I can tell from the little I do know about bird song, but greeting the sun to entice him out of the ocean.

Why does the cat purr, the rooster crow, the whale sing?

Which of these is your tune?

How and when and to what extent do resident and transient orcas, two distinct cultures of “killer whales,” communicate?

Does the heron speak to the eagle, the raven to the crows, the goat to the sheep?

How much does landscape shape language, just like it shapes culture?

Here I think of Crete, which I got to visit just about two years ago for a precious week, full of moody goddesses and gods, strong women and fragrant honey, traces of the minotaur, and sun-baked sinewy bodies like olive trees.

Compared to that reality, what did life feel like in ancient or medieval China? Sun Simiao’s writings reflect a landscape full of caves of stalactites, mountain cliffs with magic pine trees, and precious stones in hidden valleys only found by those who know. A sky full of universes within stars, each with its own heavenly bureaucracy and immortal maidens serving peaches of immortality if you only know how to dream. Deep bodies of water, abysses and caves to reflect the heavenly realm down here on earth. Magic mushrooms and Five-Stone Powder to ingest to embody the worlds and become one with them, bringing the universe, literally, inside you. The less you eat, the more expansive you become. A drop of full moon dew caught on a sacred mountain top on a copper platter engraved for magical protection and power. I play in an icey ocean to replicate the intoxicating heat surges produced by alchemical preparations. But how is it the same, and how is it not and can never be?

Zeus impregnating every maiden he can get his hands on in his islands. Men have been fondling breasts since time immemorial. Or have they? Can we recall a time before this patriarchal violence? Vikings, Greek gods, Roman armies, burning witches… but what came before? Where do my people come from? Where do any of us come from? Does it matter as we try to talk to each other?

Do orcas experience rape? Does a female orca (or a male one, for that matter, since we are looking at a culture where female whales lead) get to say no?

Expansion and contraction. Let’s bring this back to Sun Simiao and classical Chinese. Here is a passage from the introduction to Beiji qianjinyaofang 備急千金要方, volume 27 (on “Nurturing the Heavenly Nature” 養性) that I have been chewing on, to demonstrate the importance of context. It concerns the two characters 為善, which literally simply mean to “do good” or to “be good.” What does Sun Simiao mean by goodness? Let me first give you the entire paragraph for context:

扁鵲云:黃帝說晝夜漏下水百刻,凡一刻人百三十五息,十刻一千三百五十息,百刻一萬三千五百息。人之居世,數息之間,信哉!嗚呼!昔人嘆逝,何可不為善以自補邪?

吾常思,一日一夜有十二時,十日十夜百二十時,百日百夜一千二百時,千日千夜一萬二千時,萬日萬夜十二萬時,此為三十年。

若長壽者,至九十年,只得三十六萬時。百年之內,斯須之間·,數時而活,朝菌蟪蛄,不足為喻焉。

可不自攝養,而馳騁六情,孜孜汲汲,追名逐利;千詐萬巧,以求虛譽,沒齒而無厭。

故養性者,知其如此,於名利,若存若亡;於非名非利,亦若存若亡,所以沒身不殆也。

余慨時俗之多僻,皆放逸以殞亡,聊因暇日,粗述養性篇,用獎人倫之道,好事君子與我同志焉。

Biǎn Què said: According to the Yellow Emperor, in a full day and night, the water in a clepsydra drips down to the level of a hundred notches, and as a general rule a person breathes 135 times in the duration of one notch, or 1,350 times during ten notches, or 13,500 times in a hundred notches. A person’s life, in the space of counting breaths, is assured indeed! Ayaah! The ancient people, lamenting passing, how could they not have acted in virtue in order to mend themselves?

I often ruminate on the fact that one day and one night have twelve two-hour periods, ten days and ten nights have 120 two-hour periods, a hundred days and a hundred nights have 1200 two-hour periods, a thousand days and a thousand nights have 12,000 two-hour periods, and ten thousand days and ten thousand nights have 120,000 two-hour periods. This makes 30 years altogether.

If we take a person with great longevity, when they have made it to the age of ninety years, they have only received 360,000 two-hour periods. The space of hundred years a mere instant in time, to live by counting two-hour periods is something for which even the ephemeral morning mushroom or short-lived mole cricket cannot serve as adequate analogies!

How can we not preserve and nurture ourselves! And yet, we give free reign to the chase after the six emotions, relentlessly and unflaggingly, pursuing fame and fortune! A thousand pretenses and ten thousand deceits, to seek empty honors, insatiable until our last breath!

For this reason, those who nurture the Heavenly Nature, they are aware of this fact, and they do not care whether their fame and their fortune persist or perish, or whether the absence of fame and the absence of fortune persist or perish. For this reason, they are not at risk of throwing their life away.

I sigh deeply at the prevalent perversion in our current age, where people have lost all constraints and thus perish. So I have casually jotted down this crude chapter on “nurturing the Heavenly Nature” in a moment of leisure, to praise the Dao of the Five Relationships and to perform a good deed in service of the cultivated people and those of like mind with myself.

The key sentence is the last line of the first paragraph: 昔人嘆逝,何可不為善以自補邪? When I first started this translation project, I translated this rhetorical question as “The ancient people, lamenting passing, how could they not have excelled at mending themselves?” After a year of living within the world of this chapter, I have learned to read 善 “good” not as “skill” here, in the sense of acquiring a skill, becoming good at something, but as moral goodness, as virtue. Thus, based on my reading of Sun Simiao, I have corrected this line to say: “The ancient people, lamenting passing, how could they not have acted in virtue in order to mend themselves!”

Incidentally, this reading is backed up by concrete textual research like a search for the phrase 為善 in the database “Kanseki Repository,” which allows you to look up phrases by dynasty or text type. Here is an example of searching for 為善 by “Tang Dynasty”: http://www.kanripo.org/search?filter=%E5%94%90&query=%E7%82%BA%E5%96%84&type=DYNASTY). As the results there make clear, the phrase does not mean to “become good at” in the sense of improving one’s skill, but rather to “enact good deeds” since it is contrasted with terms like 為惡 “enacting malign deeds,” or associated with persons of purity 清靜者, as opposed to “stained” persons who are called 不善 "not good.”

Since you have followed my meandering thoughts all the way down to the end of this long post, here is a little concluding thought on wandering without a path and naming without words (in the Mawangdui version of this famous passage). I would really love your comments on my translation, which is admittedly pretty far out there:

道可道也。非恆道也。

名可名也。非恆名也。

無名。 萬物之始也。

有名。萬物之母也。

Dao: Paths

Yes! There are paths that can be followed as paths

But! These are not the paths that last.

Ming: Names

Yes! There are names that can be employed as names

But! These are not the names that last.

Nameless -- Embryo of the Myriad Things

Named -- Mother of the Myriad Things