Virgin Milk and Lactation in Chinese Medicine

Originally published on August 13, 2022.

This past week, I have been following a conversation on the OBAA members forum on “Lactation Insufficiency.” The practitioner who had created the original post noted that she had seen an increase in consultation requests because of the infant formula shortage in the US. In a funny coincidence, I have had a blog of my own floating around in my brain with the juicy title “Virgin Milk,” which just hadn’t gotten anywhere because I got a new stand-up paddle board and have been distracted by the gorgeous summer weather and some visitors. The final straw of the camel’s back about this topic, or third leg of the milking stool, so to speak, came a couple of days ago when somebody contacted me about presenting at a conference on the role of the heart in fertility. Be forewarned: This blog is quite long because it covers my four favorite subjects, namely goats, fertility, maternal health, and the heart.

My Good Friend Yùexìn

Each of us may just be a drop of water in the ocean of popular and biomedical discourse on “The Curse,” but bit by bit, one conversation at a time, we can take the “s” out of that awful term and think of it more like the sweet casual Chinese term 我的好朋友 “my good friend.”

Tinier than Autumn Down

In honor of the transition to the New Year of the Metal Rat and my final writing efforts of the Pig Earth year, here is little taste from the Introduction to my forthcoming Channeling the Moon, Part Two: A Translation and Discussion of Qí Zhòngfǔ’s Hundred Questions on Gynecology, Questions 15-50, which addresses miscellaneous conditions of gynecology. The following is the literal translation of a quotation from Chén Zìmíng’s 陳自明 introductory essay of the Fùrén dàquán liángfāng 《婦人大全良方》 (Compendium of Excellent Formulas for Women) composed in 1237

Classical Chinese Sleep Hygiene

This brief exploration of advice on sleep hygiene from classical Chinese medical and Daoist texts originated with my translation project on the “Hundred Questions on Gynecology.” In Question 49 on the “Thirty-Six Diseases Below the Belt,” the author discusses “harm from sleeping” as one of the seven harms that cause women’s illnesses. When a curious reviewer of my manuscript asked me to explain, I had to go down that rabbit hole, at least briefly. Here is what I found and write in my discussion…

Women’s Health in Medieval Manuscripts

In contrast to the beginnings of classical Chinese medicine in the Han period, our knowledge of early medieval medicine is still sketchy. This is due largely to a lack of sources. Of the more than 100 medical texts recorded in the Old Tang History (Jiùtángshū 《舊唐書》, 945 CE), only four have survived in the received literature from the early medieval period: Cháo Yúanfāng’s 巢元方 Zhūbìng yuánhòu lùn 《諸病源候論》 (On the Origins and Symptoms of the Various Diseases, 610 CE), Sūn Sīmiǎo's 孫思邈 Bèijí qiānjīn yào fāng 備急千金要方 (Essential Formulas worth a Thousand in Gold for Every Emergency, 652 CE, in the following discussion abbreviated as Qiānjīnfāng), his Qiānjīn yìfāng 千金翼方 (Supplementary Formulas worth a Thousand in Gold, 682 CE), and Wáng Xī’s Wàitái mìyào 外台秘藥 (Essential Secrets From the Palace Library, 752). Other texts are known only from quotations in compendiums like the Japanese Ishimpō 醫心方 (Prescriptions from the Heart of Medicine, 984 CE), a collection of early medieval Chinese medical literature by a Japanese court acupuncturist. The other great source for medical literature from this period is the corpus of medical manuscripts found in Dūnhuáng 敦煌, which date mostly to the Suí and early Táng periods.

Questioning Menopause Part Two

MENOPAUSE PART TWO: WHAT’S IN THE TEXTS?

How do the Chinese classics talk about menopause? To be meaningful, our inquiry has to be expanded a little beyond the obvious and technically correct answer: Since the concept of “menopause” does not even exist in traditional Chinese medicine or language, the medical classics do not talk about it at all.

That may be the case, strictly speaking, if we define “it” narrowly as the “pathology of age-related cessation of monthly bleeding.” As contemporary practitioners of Chinese medicine in our modern biomedicalized society, however, we still need answers for our friends, family members, and patients who come to us with conditions that they experience as pathological. So how do the classical texts discuss the aging process of women, especially in contrast to that of men? And how might these descriptions be used in the contemporary context?

Questioning Menopause Part One

“What do the Chinese classics have to say about menopause?”

It shouldn’t be such a difficult question, but for a number of interesting reasons it is.

…In regards to a potential Chinese translation for “menopause,” the only thing to note here is that this term actually has no equivalent in traditional Chinese medical (or other) texts! The closest equivalent is the concept of “a menstrual period that fails to flow through” (月經不通) or similar expressions of blockage and lack of flow/penetration.

Lower Leg Qi

The following is another excerpt from my ongoing translation project, the “Hundred Questions of Gynecology” 女科百問 by Qí Zhòngfǔ from 1220 CE. “Question Twenty-Nine: What is the Reason for Women Suffering from Pain in the Ten Toes as If They Were Being Fried in Oil, and Experiencing Heat Pain When Covered up and Cold Pain When Exposed to Blowing Wind?” … The key points to take away from earlier medical literature on the disease of Lower-Leg Qì are as follows: It is a condition that can express itself in numerous ways and does not have a single cause or even key symptoms. Nevertheless, it is, at least was originally, associated with pathological wind that invades the body through the feet. …

Traditional Chinese Gynecology in the West

In the context of my most recent book publication, a translation and discussion of the first section of an important thirteenth century text on gynecology, I have been thinking a lot about the current state of clinical practice of what I call “traditional Chinese gynecology” in the West. To be frank, for years now I have been hearing or reading statements that are appalling to me in their arrogance and ignorance vis-a-vis what I consider one of the crowning achievements of traditional (note the small “t”) Chinese medicine.

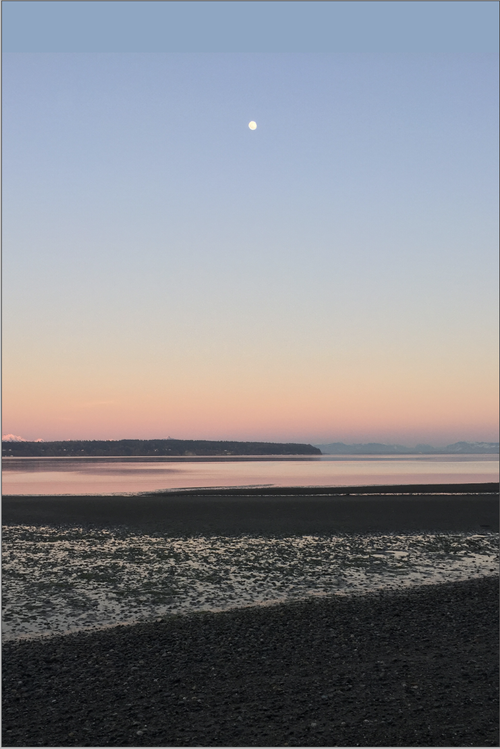

Sun Simiao on Fertility

The following is an excerpt from the 75-page historical introduction to my newest publication Channeling the Moon, a translation and discussion of the first fourteen questions of Qí Zhòngfǔ’s 齊仲甫 Nǚ Kē Bǎi Wèn 女科百問 (“Hundred Questions of Gynecology,” published in 1220 CE). This excerpt includes a brief introduction to the Bèi Jí Qiān Jīn Yào Fāng 備急千金要方 (composed by Sūn Sīmiǎo 孫思邈 in 652) and a survey of Sūn Sīmiǎo’s ideas on fertility. For more on early Chinese gynecology and fertility, see the information page for my book Channeling the Moon in my ONLINE BOOKSTORE HERE. The photographs below, most of which have also made it into the book, are from around my home on Whidbey Island, but here you get the colored version.

Misogyny in Chinese Medicine

As a scholar who has closely studied and translated the works of Sun Simiao and early Chinese gynecological literature for several decades, the time has finally come for me to clear up mistaken views about this important figure and his work that I encountered some years ago. Given Sun Simiao’s significant contributions to Chinese medicine and to gynecology, he deserves to have someone speak up for him.

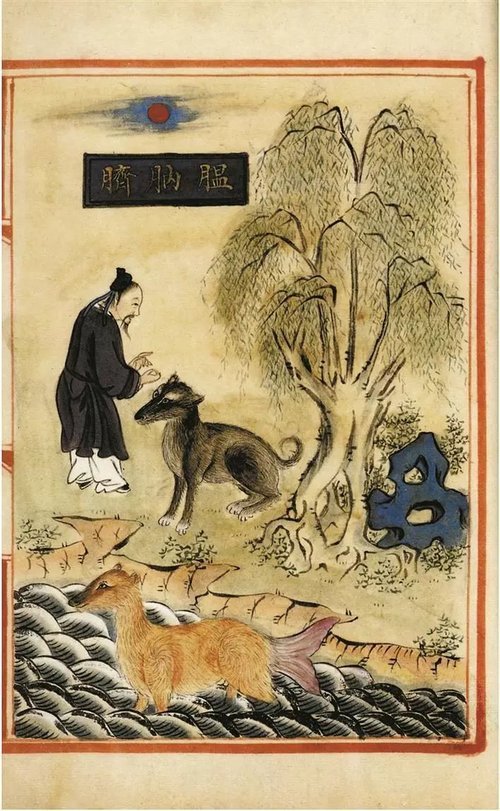

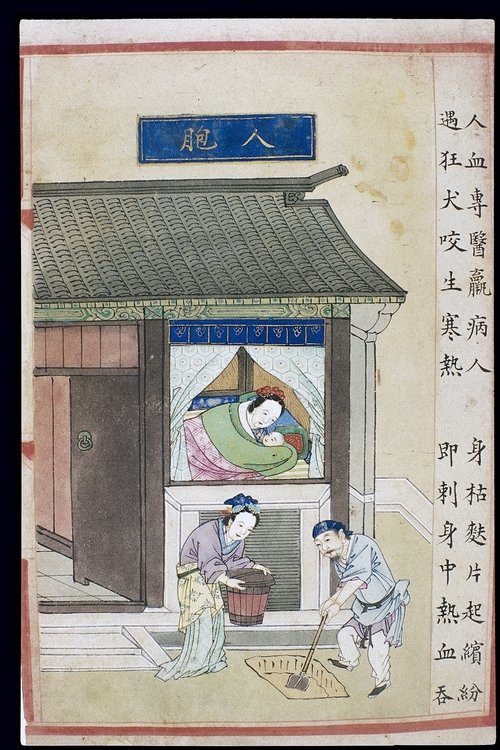

Seal Penises and Testes

The following is an excerpt from my current book project, a translation and discussion of Qí Zhòngfǔ’s 齊仲甫 Nü Ke Bai Wen 女科百問 (A Hundred Questions in Gynecology), published in 1220. It is one of two formulas attached to Question Sixteen:

A Lactation Consultant’s Perspective on Placentophagy

Guest blog by Sarah Hollister, RN, PHN, IBCLC: As a nurse and an International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC), I have the opportunity to work with nearly every pregnant woman and new mom and baby at a group of four primary care health centers in Northern California. I would like to share my experience, concerns and request for collaboration to closely examine the new practice of placenta encapsulation, as it has grown to become a component of the postpartum experience for the new moms who I work with and throughout the United States. I have encountered assumptions that placenta consumption increases milk production, is a prevention for postpartum depression, and has existed in history as an ancient human practice. I will provide a summary here of the work I do and what I have found with my clients involving this practice.

Placentophagy and Chinese Medicine

Disclaimer: The following blog is merely a collection of notes and not a serious scientific research paper. There is obviously a pressing need for more research. My intention with this blog post is not to make any conclusive statements about the practice of placenta encapsulation or placentophagy, which I am not qualified to do anyway, but merely to offer the classical Chinese perspective as an urgently-needed correction to some misinformation promoted in popular and Chinese medicine circles.

Fertility and Gynecology: Biomedicine, Chinese Medicine and Common Sense

Let me start by quoting the obvious (from Sun Simiao’s Bei Ji Qian Jin Yao Fang, vol. 5 on Pediatrics:

故今斯方,先婦人、小兒,而後丈夫、耆老者,則是崇本之義也。

“Now the present collection of treatments is arranged by placing the treatments for women and children first, and those for husbands and the elderly afterwards. The significance of [this structure] is that it venerates the root.”