On Walls, Part Two: The Great Wall of China

Originally published March 22, 2017

不到長城非好漢

If you haven’t climbed the Great Wall, you are not a real hero. (poem by Mao Zedong, 1935)

This blog is a continuation of my previous post, “Why I Dislike Walls, Part One,” which you can read here. That post was an attempt to give voice to some of my personal experiences with walls in Germany and on the US-Mexican border, to explain my personal gut reaction. In the present writing, I am putting on my supposedly objective historian’s hat for Part Two, to look more closely at arguably the most famous historical example of wall-building, namely the Great Wall of China. So let us travel far away in time and space, to fifteenth-century China and the construction of the Great Wall in the Ming dynasty. And here I’d like to add the disclaimer that I am not a specialist in late imperial Chinese history, but merely get to revisit this topic once a year while teaching a survey course on Chinese History and Culture to students of Chinese medicine at the National University of Natural Medicine. My original inspiration for this topic came from a brief lecture that Professor Donald Harper gave more than two decades ago at the University of Arizona in an undergraduate Chinese Civilizations class, for which I served as a Teaching Assistant. All mistakes are of course my own.

Yongle Emperor (r. 1402-1424)

For those of my readers who are less familiar with Chinese history, the Ming dynasty was the last great indigenous Chinese dynasty, picking up the pieces after the collapse of the traumatic Mongol Yuan dynasty in 1368. The early Ming period was marked by cultural and territorial expansion and great wealth and power, occurring at a time when Europe was suffering from a series of famines and revolts, the Black Death (1346-1353) in the aftermath of the Mongol invasion, and the Hundred Years’ War between England and France (1337-1453). Less than a century before the beginning of the European Age of Exploration in the late 1400s and Vasco Da Gama’s arrival in India in 1498, the Chinese Yongle emperor sent a Muslim eunuch, the great Admiral Zheng He, on a series of seven naval expeditions from 1405 to 1433 that took him all the way from the shipyards in Nanjing through the Indian Ocean past Arabia to Africa.

According to Chinese records and confirmed by European and Arab accounts, his flotilla consisted of 27,000 men in 62 enormous unrivaled “treasure boats” 450 feet long and 180 feet wide, with nine masts, four decks, and accommodating 500 people each, and about 200 smaller ships.

As the illustration to the left, which compares one of these treasure boats to Columbus's Santa Maria, no other ships in the world came even close to these dimensions until the construction of ships with iron hulls in the nineteenth century.

The painting of the giraffe that you see to the right in my mind demonstrates one of the great stories of world history: The Chinese imperial court financed the construction of these boats and the expeditions for which they were used for the expressed purpose of carrying out tributary missions, to demonstrate the grandeur of the Ming emperor. Not directly interested in trade, since in the Chinese eyes the rest of the world did not have much to offer, the most notable achievement of Zheng He’s missions was the arrival of a giraffe at the Ming court. This animal was interpreted as an auspicious omen, namely the appearance of a qílín 麒麟, a sort of Chinese unicorn hailed as a symbol for Heaven’s approval of the Ming emperor. By all accounts successful and running into no opposition to speak off, these expeditions were abruptly called off upon Zheng He’s return from the seventh journey, the ships were abandoned, the shipyards dismantled, and the Ming dynasty turned inward. Shortly afterwards, the new Ming emperor was captured by the Mongols in 1449 and the Ming dynasty turned inward, strictly limited all contact with the outside world, and began the construction and fortification of a great wall to protect it from its northern neighbors.

Portuguese in Japan, 17th century

Filling this power vacuum and forced by the collapse of the Pax Mongolica, the Black Death, and the expansion of the Ottoman Empire to find new trade routes to Asia via the sea, the Europeans started knocking on China’s borders shortly thereafter, reaching India in 1498 and arriving in Japan in 1543. After decades of decline, fiscal collapse, and rebellions from internal and external enemies, the last indigenous Chinese dynasty was finally brought to an ignoble end in 1644 when a Chinese general opened a gate in the supposedly impenetrable Great Wall to allow the invading Manchu army into China. Instead of enthroning the Chinese general, as he had expected, the Manchus promptly got rid of him and founded their own great Qing dynasty. This ushered in another age of peace and prosperity in China, albeit under foreign rule, until the destruction of the Opium Wars and Western colonialism in the 1800s.

Besides these fascinating (and depressing) tidbits of what is perhaps the most “real” aspect of the story of the Great Wall, what other lessons can we take away from the Great Wall of China?

筑就長城千夫苦 -- 何止孟姜一人哭。

Construction of the Long Wall made a thousand workers suffer. How could the crying be limited to a single person, to Lady Mèng Jiāng alone?

Let us look at some other stories, from other times in history, beginning all the way back with Qin Shi Huangdi, the first emperor of the Qin dynasty who unified China in 221 BCE. As part of his grand enterprise of uniting the formerly divided feudal states under his thumb, he actually deconstructed most of the walls that he encountered in his new empire, only enforcing small segments at the northern border. Regardless of this historical fact, one story about wall-building in the Qin dynasty continues to be told to this day, based on a Ming dynasty elaboration on a Tang dynasty variation on an originally unrelated tale of a virtuous woman who properly grieved her husband’s death. In this version of the story, the Great Wall stands as a symbol for the folly and cruelty of the first Qin emperor who conscripted untold masses of suffering peasants into cruel corvée labor to complete his megalomaniacal construction projects.

Lady Mèng Jiāng crying her husband's bones out of the wall.

Lady Mèng Jiāng was the unfortunate wife of one such laborer who had been taken away from his loving wife to die from the deprivations of forced labor on the wall. Worried about her husband, Mèng Jiāng went looking for him and cried such bitter tears of grief when she arrived at the wall and found out about his death that she actually caused the wall to collapse and reveal her husband’s bones, which had been buried in the wall. It is obvious how certain factions at the Ming court would have used this story to express their opposition to the xenophobic Ming policies of turning inward and expending large amounts of sparse and sorely needed cash on the construction and maintenance of a wall in a futile attempt to keep foreigners out. And history certainly proved them right since the wall stopped neither Mongols nor Manchus from invading, and eventually destroying, the collapsing Ming empire.

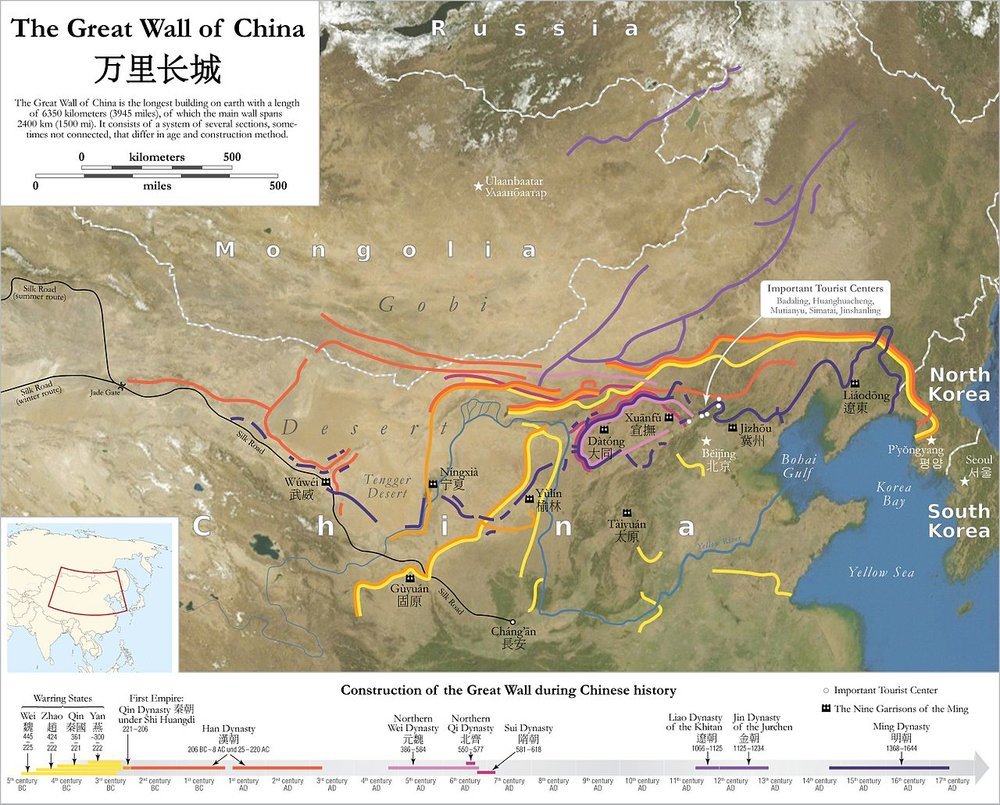

Before we look at more modern Chinese interpretations of their Great Wall, let us briefly consider its reception in the West. Interestingly enough, and confirming the historical fact that the Great Wall of China as we know it is not two thousand years old but only dates to the fifteenth and sixteenth century, no mention is made of it by Western travelers under the Mongol rule. This is vividly illustrated in this map of the Great Wall, which shows the different walls color-coded by their construction periods.

Beginning in the seventeenth century, early European accounts, in particular those by the highly educated Jesuit visitors to the Qing imperial court in the capital of Beijing, described the Ming wall in glowing terms. The grandness of the wall served to vividly illustrate their argument that China was a mythical country ruled by an ancient monarchy with an enlightened philosopher king at its helm, presumably in the hope to gain more funding for their China mission.

Jesuit missionary's painting, 1853

In their enthusiasm for what they still experienced in the early Qing period as a highly advanced civilization with great wealth, literacy, political power, and cultural and technological achievements, they exaggerated its size to the point where it became known in the popular imagination of the eighteenth century as one of the Seven Wonders of the World and as the only human-made structure visible from the moon, greater than the pyramids of Egypt, containing enough stone to build two walls around the earth’s equator and snaking over hills like a balance to the milky way in the sky. The picture below from Ripley’s Believe it Or Not says it all….

Ripley's Believe it Or Not, 1932

In the nineteenth century, the perception of China in the West changed dramatically. It was no longer a glorious advanced enlightened civilization full of silk, tea, porcelain, and gentile philosophers in manicured gardens with graceful pavilions and weeping willows. Instead, it became an ossified empire in decline, mired in conservative xenophobia, Oriental despotism and misogyny, with foot-binding, concubinage, opium addiction and corruption in the elite, and below teaming with starving and diseased masses in need of salvation by missionaries, doctors, Colonial powers, traders, and gunboats. In this context, the Wall served to demonstrate the cruelty of the First Qin emperor and the oppression of both the laboring masses and of women in particular, in the legend of Mèng Jiāng.

Returning now to China in the twentieth century, the wall became a powerful symbol for Chinese nationalism and anti-Manchu and anti-Japanese sentiments. In addition, Chairman Mao liked to compared himself to Qin Shi Huangdi as another great historical unifier of China.

In this context, Mao used the wall as a symbol for the greatness, unity, technological achievements, and fighting spirit of the Chinese people.As part of the condemnation of Confucianism and its traditional family values during the Cultural Revolution, on the other hand, our poor lady Mèng Jiāng was denounced as a feudalistic and selfish enemy of the people, obstructing the grand construction project of the Qin emperor. The Great Wall of China may not be as long or great or old as it has tended to be in both Western and Chinese imaginations. Regardless of this discrepancy between fact and fiction, Mao’s present of a 36-feet long tapestry of the Great Wall to the United Nations in 1974, when the People’s Republic took over the seat from the Republic of China in Taiwan, is an evocative symbol that each of us is free to interpret in any way we want. Similarly, I leave it to you, dear reader, to choose which of these lessons from China’s Great Wall you may want to apply to our own contemporary situation.