Impressions of the SHennong Bencaojing

Originally published on Feb 22, 2016

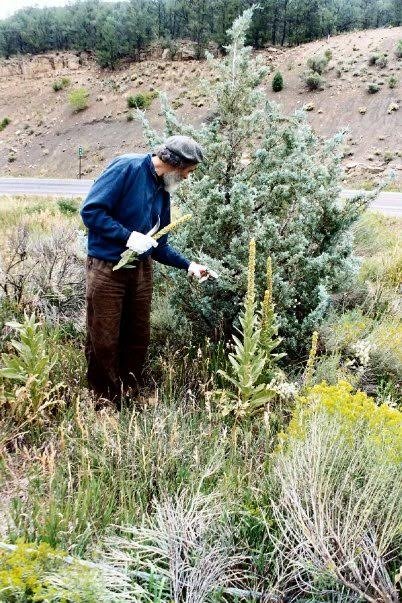

What follows is a contribution by Z'ev Rosenberg, L. Ac. (Professor, Alembic and Xinglin Institutes, and Chair Emeritus, Pacific College of Oriental Medicine, San Diego, Ca.). Z'ev and I became good friends traipsing through the woods around Taos, New Mexico doing an herb walk class, "nerding out" about local medicinal plants and their relationship to classical Chinese herbs.

IMPRESSIONS OF THE 神農本草經 SHEN NONG BEN CAO JING

BY Z’EV ROSENBERG, L. AC.

I often tell people that I started practicing Chinese medicine before it was a profession in the West, back in the early 1980’s! I never thought that it would be a vocation that could make a living, and looking back from the present, the growth has been explosive, but in many ways, not what I and others of that generation of practitioners (the first in the U.S.) thought it would be.

The profession, unfortunately called ‘acupuncture’, a modality, instead of Chinese or East Asian medicine, has been struggling in its direction forward, with many different points of view from total biomedicalization, to integrative medicine, to a return to a more ‘classical’ approach.

One of the main problems has been the precedents that were set four decades ago, in schools and licensure. With a limited base of knowledge, a lack of reliable translations of important Asian medical texts, and a lack of connection with Asian schools and authoritative physicians, the profession had to ‘grow up in public’, and figure it out as we went along. It was like building a house or apartment building without a solid foundation, so that as the building grew upwards, it became more unstable.

Without training the minds of students and new practitioners in the actual logic, methodology, language and culture of Chinese/East Asian medicine, it is human nature to fill those gaps with biomedical/’scientific’ thinking, and to seek other modalities such as Western nutrition, naturopathy, functional medicine, Western orthopedics, and supplements. Further compounding the problem is the small percentage of our profession who have been trained in or practice internal/’herbal’ medicine, apparently less than ten percent. Students also do not realize that what is called ‘Traditional Chinese Medicine’ is a synthesis of the twentieth century in China designed to create a complimentary health care and college training system to Western medicine, where illnesses and treatment strategies are often correlated to Western diseases, rather than traditional categories.

So what is one answer to this conundrum? It is to reestablish the roots of the Chinese/Asian medical field, by embracing its core principles. 理論 Li lun/principle and theory are foundation of all fields and scientific endeavors, and it is the principles of Chinese medicine (yin/yang, five phases, channel theory, along with the principles of medicinals (flavor, qi, direction, combination and preparation) that must be mastered and understood in order to properly practice Chinese/Asian medicine.

Fortunately, we are now in an era where the core medical texts, the Han dynasty medical classics, are being released in definitive, clear versions with more accurate terminology. This trend began with the release in the 1990’s of the Practical Dictionary of Chinese Medicine, with several thousand technical terms, now available in expanded form in such iOS and Android apps as Pleco, along with many other Chinese/English dictionaries, books for learning medical Chinese, and courses. Along with the availability of studying medical Chinese language, many Western practitioners now go to China, Taiwan and Japan to study authentic forms of the medicine. In the last few years, we have seen the 傷寒論 Shang han lun, 金匱要略 Jin gui yao lue (translated by Sabine), 素問 Su wen, and soon the 靈樞 Ling shu and an updated 難經 Nan jing from Paul Unschuld.

At the same time, study programs in 古方 gu fang/’ancient prescriptions’ from such teachers as Huang Huang, Arnaud Versluys, and Suzanne Robideux are now available, along with classical acupuncture and moxabustion courses by such teachers as Lorraine Wilcox (who has translated or edited several acupuncture classics), Ed Neal, and David White.

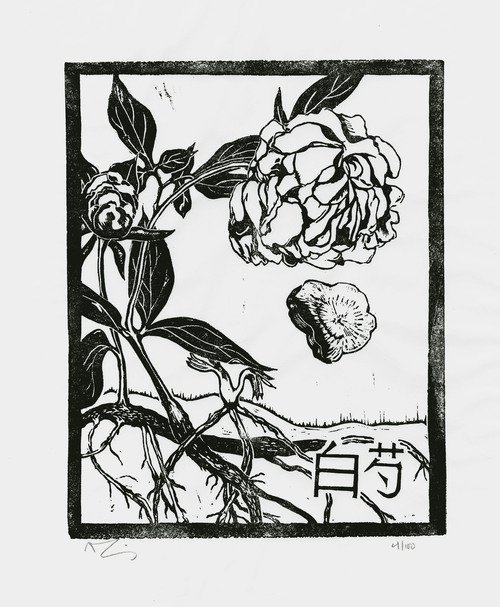

The most recent addition to our ‘embarrassment of riches’ in English translation is Sabine Wilm’s latest work, 神農本草經 Shen nong ben cao jing/The Divine Farmer’s Classic of Materia Medica. With the publication of this work, a complete set of Han dynasty medical classics is now available for the serious student and practitioner. What is special about this translation, and text, can be summed up in the word ‘core’. It is the earliest compilation of the internal medicine tradition, including 365 herbs, minerals and animal parts divided into three categories, 上藥 shang yao/superior/upper medicinals, 中藥 zhong yao/middle-grade medicinals, and下藥 xia yao/lower (inferior) medicinals. What is quite interesting about this classification is that the medicinals that are the least 毒 du toxic/imbalanced are in the superior category, suitable for 養生 yang sheng/nourishing life, supplementing qi, blood and 精 jing/essence, and maintaining health and longevity. The middle and inferior categories contain more ‘medicinally active’ herbs that must be combined with other medicinals to balance their extremes or reduce toxicity and side effects, and are more suitable for treating illnesses. This reminds us that the vast system of Chinese/Asian medicine in its foundation is about preserving, nurturing and maintaining health, and only secondarily about treating disease. As it says in the preface to book one, ‘Upper Medicinals’, “The upper-level medicinals consist of 120 types. These function as rulers. They are in charge of nurturing 命 ming/destiny and thereby correspond to Heaven. They are non-toxic and (even) when taken in large quantities or over a long time, do not harm the person. If you want to lighten the body, boost qi, avoid aging, and extend your lifespan, root your prescriptions in the upper (section of the) Classic.” Section two discusses the fundamental rules of combining medicinals into formulas, in their mutual relationships, as “rulers, vassals, assistants, and messengers”. Section three of the preface discusses the flavors of the medicinals, harvesting, processing, delivery systems (pills, powders, decoctions) and preparation of the medicinals. The remaining sections (four through seven) cover dosages, categories of illness, and diagnostics.

Happy Goat Productions has produced this book in a physician’s desk-friendly format, compact, easy to carry and access, and with clear, readable fonts. The woodcuts and drawings that illustrate the text are a delight as well. For those of us who are practicing wild-crafters or gardeners, or ‘whose hands are constantly busy with herbs’, the simple, precise discussions of the 365 medicinals is a sheer delight, and constant inspiration.

What would I recommend for future editions? Sabine had a monumental job putting together this text, it was no walk in the park. In fact, it was often written in a cabin warmed by a wood-burning stove, in the howling frigid winds that blow down the Columbia gorge from the east in the wintertime. But I’d personally love to see commentaries on the text in an expanded edition, along with more numerous illustrations. Otherwise, this text should be on every herbalist’s desk, and would also serve as an excellent introduction to herbal medicine for acupuncture/ ’moxabustionists’ as well. I’m looking forward to taking the Shen nong ben cao jing into the forests, as I commune with the plants and minerals in the fields. Or as Zhuangzi once said, ‘cloud hidden, whereabouts unknown’.

Z’ev Rosenberg, 醫生 yi sheng,

San Diego, Ca., Spring 2016, year of the fire monkey